What is Urban Planning?

Britannica Academic1 describes the process as:

“design and regulation of the uses of space that focus on the physical form, economic functions, and social impacts of the urban environment and on the location of different activities within it. ….an endeavor involving political will and public participation”

The history of urban planning occurs alongside the history of the city as such planning is evidenced at some of the earliest known urban locations2.

Caernavon (Wales) John Speed 1611

The towns and cities of the medieval and Renaissance time period followed the pattern of the village. Streets were merely footpaths that served the need for interaction rather than for transportation1. Planning and architecture grew organically and often chaotically however from the 15th century on architecture and urban planning progressed to a more refined agenda with the development of theoretical treatises for proper planning and design of towns and cities.

The turn of the 20th century brought a rapid growth of industrialized cities with the style of its construction largely dictated by the needs of the private market. The structure and arrangement of the city without regulation led to factories encroaching on residential areas, tenements crowding, and skyscrapers dominating over other buildings1. The advent of zoning regulations, first instituted in the early 20th century, sought to eliminate property value decline

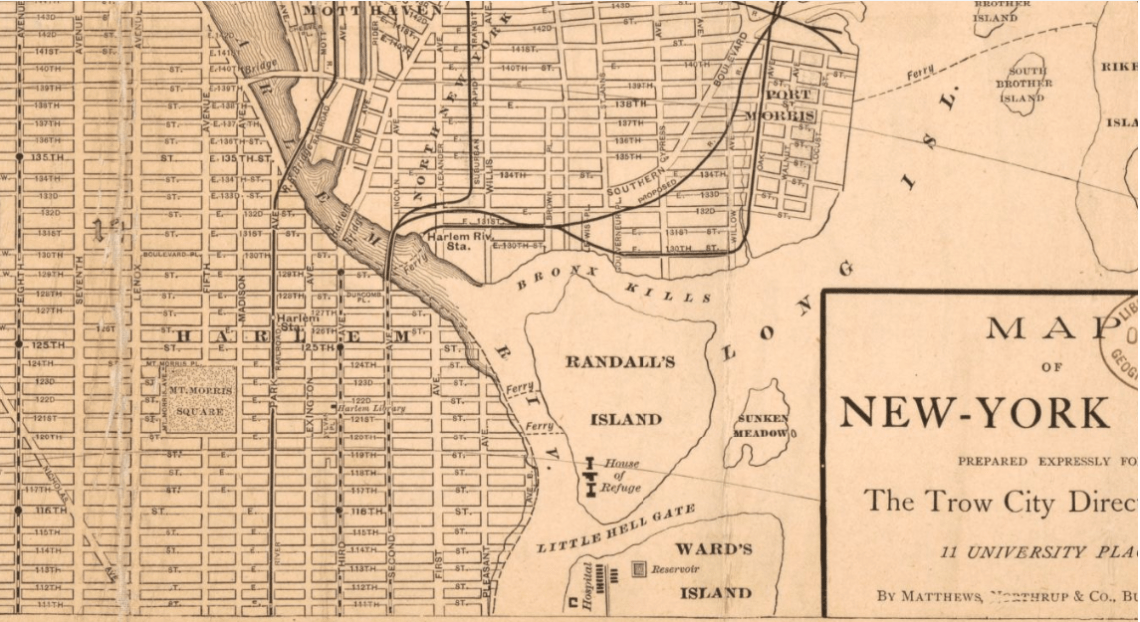

Library of Congress Map of New York City3

The 1916 Zoning Resolution of New York was the first zoning regulation in the country4 and was developed by a committee led by George McAneny, the borough president of Manhattan who made the following declaration in the necessity of regulation:

“to arrest the seriously increasing evil of the shutting off of light and air from other buildings and from the public streets, to prevent unwholesome and dangerous congestion both in living conditions and in street and transit traffic, and to reduce the hazards of fire and peril to life.”

The approaches to zoning have evolved over the years as urban planning theory has changed along with political priorities. Currently there are four broad categories of zoning approaches:

Despite the development of progressive zoning approaches, the US remains stagnant in its use of the same Euclidean zoning approach that was established 100 years ago. It is predominant in most of North America in spite of criticism in its lack of progression towards dealing with the increasing complexity of social, political and environmental challenges in cities. Euclidean zoning, also known as single-use zoning has been implicated as a causative factor in the development of urban sprawl, urban decay, environmental pollution, increased crime and violence, racial and socioeconomic segregation as well as reduced quality of life. Clearly the status quo of a 100-year-old zoning approach is no longer appropriate given the knowledge we have today regarding its unethical byproducts. A more innovative approach to zoning regulation which embodies an understanding of socioeconomic determinants of health would be a more holistic and effective method in reaching the goals of sustainable economic prosperity.

Although zoning regulations play a large role in the development of urban related problems, transportation ambitions and regulations also carry some responsibility for the issues we see today. Transportation networks that cater exclusively to automobiles reduces the opportunity for healthier lifestyle options such as walking or biking. Gary Toth describes his professional beliefs in his first twenty years as a transportation planner “the solution to congestion was to build more and bigger roads. We felt we were not doing our jobs properly unless enough lanes were added to ensure free flowing traffic 24/7, 365 days a year”. Community engagement led Toth to understand the conflicting interests that transportation professionals have with the communities they are serving5.

Who has final decision-making power in US cities?

The mayor and city council have primary responsibility for routine planning functions and utilize an independent planning commission of appointed members for guidance. Economic prosperity remains central to the efforts of city planners with planning commission members negotiating deals with private developers. These include offering land, tax forgiveness, or regulatory relief to property developers in return for investment commitment or provision of amenities1.

As community engagement was vital for Gary Toth to understand existing conflicts of interest in his profession as a transportation planner, it remains a vital aspect in shaping policy. All parties that are affected by urban development including local residents should be actively involved in shaping the policies of urban planning. City council meetings allow public comment with preliminary filing of speaker request forms and would be an appropriate venue to begin a participatory discussion.

References:

1. Urban planning. (2018). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from: http://academic.eb.com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/levels/collegiate/article/urban-planning/74444

2. Kadish, G. E. (1968). A history of egyptian architecture. the first intermediate period, the middle kingdom, and the second intermediate period (book review)10.2307/988437

3. Library of Congress. (2018). Map of new york city 1889. Retrieved from https://www-loc-gov.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/resource/g3804n.ct006580/

4. New York Times. (2018). Zoning arrived 100 years ago. it changed new york city forever. Retrieved from https://www-nytimes-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/2016/07/26/nyregion/new-yorks-first-zoning-resolution-which-brought-order-to-a-chaotic-building-boom-turns-100.html?_r=0

5. Project For Public Spaces. (2018). Transportation in the U.S.: A look back, and forth. Retrieved from https://www.pps.org/article/backtobasicsintransportation

Hi Deb,

You chose an interesting blog topic to discuss. I think having more bike and walking paths within a community is a great way to get people out of the house and moving more. I can see how it is hard to do outdoor activities if the city design is only focused on cars as the main form of transportation. The community I live in right now has some good walking paths and areas to bike in, but I fear it may be shrinking soon because I can see all sorts of new construction sites for retail and condo areas. I understand the need for new development, but I worry about the safety of pedestrians and bikers as new construction will mean more cars. Looking at crash data for the state of Arizona from 2016, it shows the number of car crashes steadily increasing over the years. 81.4% of crashes in AZ for 2016 were in urban areas (AZ Department of Transportation, 2016). Overall, I agree that there should be better urban planning to create spaces for more outdoor activities. How did you become involved with this issue? I know in Montana the local community has come up with a fun way to help build a community-wide trail system. A community nonprofit group organizes Ales for Trails events with music, food trucks, and beer tasting and the profits are given to help build the trail system. Billings TrailNet (n.d.) supports policies that fund trails to encourage healthy lifestyles.

References

Arizona Department of Transportation. (2016). Arizona motor vehicle crash facts [PDF

document]. Retrieved from http://azdot.gov/docs/default-source/mvd-services/2016-crash-

facts.pdf?sfvrsn=6

Billings TrailNet. (n.d.). Who we are. Retrieved from https://billingstrailnet.org/who-we-are-3/

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading your post about urban planning and the different zoning approaches utilized in the U.S., especially Euclidean zoning. You mentioned several downfalls to this zoning approach including urban decay, environmental pollution, and increased crime and violence. Is there a more innovative approach, perhaps utilized in another country, that you think would improve economic prosperity, improve health outcomes of individuals, and benefit the environment here in the U.S.?

The Health Impact Assessment (HIA) tool can be utilized to help improve public health through community design (CDC, 2016). This tool helps predict how populations will be affected by policies, programs plans, and projects as it applies to anticipated changes in community design (CDC, 2016). The Arizona Department of Health Services (ADHS) designed and implemented the AzHealthy Communities Program which utilized the HIA statewide (CDC, 2017). Additionally, the CDC’s Healthy Community Design Initiative provides federal expertise regarding health considerations to individual states undergoing transportation and community planning transformations (CDC, 2016). While this tool has the ability to improve health outcomes of individuals in the U.S., its use is not mandated (CDC, 2016). However, if used in conjunction with public health assessments, health risk assessments, and environmental impact assessments that are oftentimes required by law, I believe the environment and individual health outcomes would improve nationwide.

Additionally, Complete streets policies are implemented in 33 states throughout the U.S. which provides safe walking and biking plans into transportation design (The State of Obesity, 2018). The Vitalyst Health Foundation is working with Phoenix to build Complete Streets and has already passed two city ordinances to improve walking and bike safety measures in the Phoenix area in order to achieve the overarching goal of improving health outcomes of people living in AZ (State of Obesity, 2018).

Are there any additional initiatives, assessment tools, or policies utilized in AZ that you know of that influence community design and consider community health outcomes? As an APN, how can you contribute to improving urban planning processes in order to enhance individual health outcomes of the patients you will care for in the future?

References

CDC, (2017). Arizona department of health services. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/fundedhias/arizona.htm

CDC, (2016). Health impact assessment. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/hia.htm

The State of Obesity, (2018). Complete streets. Retrieved from http://www.stateofobesity.org/state-policy/policies/completestreets

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing the Health Impact Assessment tool. As far as other initiatives, ADOT has a statewide bicycle and pedestrian plan below is a link to a recent update.

Arizona Department of Transportation. (2013). ADOT statewide bicycle and pedestrian plan update. Retrieved from https://apps.azdot.gov/files/ADOTLibrary/Multimodal_Planning_Division/Bicycle-Pedestrian/Bicycle_Pedestrian_Plan_Update-Final_Report-1306.pdf

LikeLike

Thank you for discussing this important topic in such an accessible manner. Your post brought a few concepts to mind: the epidemiological transition, social determinants of health, and power differentials. Based on the history that you provided, urban planning seems central to the health of communities and populations. Historically, the late 19th-early 20th centuries saw the U.S. shift from a society characterized by high mortality due to infectious diseases to increased life expectancy with a rise in the burden of chronic conditions. This epidemiological transition was driven in large part by improved living conditions, access to healthy food and clean water, as well as sanitary sewage systems. All these factors are integral to urban planning (Weitz, 2017). Furthermore, as Euclidian planning is implicated in urban sprawl, decay, pollution, violence, and socioeconomic segregation, one can further appreciate how urban planning policy can either promote or mitigate social injustice and thus influences social determinants of health (Levy, 2013). Regarding the crafting of urban planning policy, one must consider that policymaking is essentially a marketplace of ideas (Longest, 2014). Those with the ability to bargain, i.e. have access to power and/or resources, will most likely set the agenda and drive the policymaking process. Due to the nature of our relatively static living situations-as opposed to nomadic existence-urban planning policy has direct, daily, and long-standing effects on the people living in a given area. As you elucidated, the environment continues to influence our wellness long after decisions have been made and policy implemented. One question is: How to counter power differentials and ensure equity in the agenda setting and policymaking process? This may be a point of leverage to address issues of health equity in a community over generations.

References

Levy, B. S., & Sidel, V. W. (2013). Social injustice and public health. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Longest, B. B. (2014). Health policymaking in the United States. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press.

Weitz, R. (2017). The sociology of health, illness, and health care: A critical approach. Boston, MA: Cenage Learning.

LikeLike